Wednesday, 3 October 2012

Sabanis Canoes or Boats

My last entry was a guest blog from Douglas Brooks, who is working on a sabani in Okinawa. He is maintaining his own blog of the project which makes good reading. Consider this post a complement to Douglas's blog.

The day after Douglas's guest post here, I discovered in my possession a booklet on sabanis which had been loaned to me by my colleague Ben Fuller, curator at Penobscot Marine Museum in Searsport, Maine. SABANI Canoes of Okinawa, by Katsuhiko Shiraishi, appears to have been self-published (in 1985, I believe, but I can't find the data now). The text is in both Japanese and English, and although the English translation is, unfortunately, awful, the illustrations are very nice indeed. (The cover is shown below; all images in this post are from the same source.)

Whether the sabani is a "canoe" or not is debatable. On the pro side of the argument, it clearly evolved from a dugout canoe. The bottom is a massive cedar dugout, to which one side strake is added on each side (plus small partial strakes to raise the freeboard at the bow and stern. As Douglas Brooks noted, the strakes, too, bear a relationship to dugout practice, as they are not milled lumber, but hewed to shape.

Whether the sabani is a "canoe" or not is debatable. On the pro side of the argument, it clearly evolved from a dugout canoe. The bottom is a massive cedar dugout, to which one side strake is added on each side (plus small partial strakes to raise the freeboard at the bow and stern. As Douglas Brooks noted, the strakes, too, bear a relationship to dugout practice, as they are not milled lumber, but hewed to shape.On the other hand, it seems wrong to call anything a canoe that features such massive construction overall, and its shape is hardly canoe-like -- more banks-dory-like in its half-breadths, while the fish-form plan view is unique.

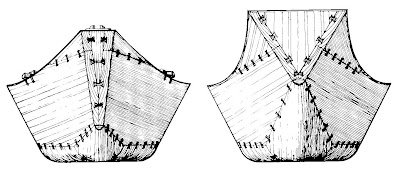

There is a very narrow triangular bow transom that might be considered a stem instead. The stern transom is very close to an equilateral triangle. All pieces are fastened together with dovetail keys, alternating on the inside and outside of the hull. Between each dovetail key is a bamboo nail driven at a very steep angle through one of the exposed plank surfaces so that it edge-nails the bottom to the strakes. (I can't tell if bamboo nails are used similarly at all other joints, or just the bottom-to-side joint.)

There is a very narrow triangular bow transom that might be considered a stem instead. The stern transom is very close to an equilateral triangle. All pieces are fastened together with dovetail keys, alternating on the inside and outside of the hull. Between each dovetail key is a bamboo nail driven at a very steep angle through one of the exposed plank surfaces so that it edge-nails the bottom to the strakes. (I can't tell if bamboo nails are used similarly at all other joints, or just the bottom-to-side joint.)In the image below, the bow is on the left. The stern is considerably higher, to help the stern lift with following waves, according to Shiraishi.

Construction begins by fastening the ends of the strakes together, then forcing the strakes apart amidships, which produces a nice curved sheerline. Then the dugout bottom is carved to shape to sit on the bottom edges of the strakes -- as Douglas Brooks noted, this is opposite to the common procedure for producing an extended dugout, in which the dugout is produced first, as a base, and then strakes are added to build up the sides.

Construction begins by fastening the ends of the strakes together, then forcing the strakes apart amidships, which produces a nice curved sheerline. Then the dugout bottom is carved to shape to sit on the bottom edges of the strakes -- as Douglas Brooks noted, this is opposite to the common procedure for producing an extended dugout, in which the dugout is produced first, as a base, and then strakes are added to build up the sides. On the "it's a canoe" side of the argument, sabanis are paddled, not rowed, as shown below in the picture of a racing version of the boat, used at an annual festival in Okinawa. Note the unusual hand position on the gripless paddle: with the thumbs facing each other. Note also how the flat face of the paddle blade is not the power face.

On the "it's a canoe" side of the argument, sabanis are paddled, not rowed, as shown below in the picture of a racing version of the boat, used at an annual festival in Okinawa. Note the unusual hand position on the gripless paddle: with the thumbs facing each other. Note also how the flat face of the paddle blade is not the power face. Shiraishi repeatedly stresses that, due to its narrow beam, the sabani is a fairly unstable boat, prone to capsize especially under sail. (But very pretty under sail, as the image below shows.) It is, however, fairly easy to recover from a capsize. Due to their voluminous wood construction, the raised ends have considerable buoyancy, making the canoe unstable in an inverted position as well. The boatmen turn the boat broadside to a wave and then can easily flip the boat upright. Then they turn it again to face the waves and wait for the bow to lift on a wave while then apply downward pressure on the stern, thus allowing the water to sluice out over the transom. Climb in again, and off they go.

Shiraishi repeatedly stresses that, due to its narrow beam, the sabani is a fairly unstable boat, prone to capsize especially under sail. (But very pretty under sail, as the image below shows.) It is, however, fairly easy to recover from a capsize. Due to their voluminous wood construction, the raised ends have considerable buoyancy, making the canoe unstable in an inverted position as well. The boatmen turn the boat broadside to a wave and then can easily flip the boat upright. Then they turn it again to face the waves and wait for the bow to lift on a wave while then apply downward pressure on the stern, thus allowing the water to sluice out over the transom. Climb in again, and off they go. As an aid to turning the capsized boat upright, the mast is easily removed. Note how a pair of easily-removed wedges secures the mast through a square hole in the thwart. Note also the multi-position mast step, which allows the mast to be angled forward or back, depending on the point of sail.

As an aid to turning the capsized boat upright, the mast is easily removed. Note how a pair of easily-removed wedges secures the mast through a square hole in the thwart. Note also the multi-position mast step, which allows the mast to be angled forward or back, depending on the point of sail.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment